S. M. Grubb: “Why I Am a Mennonite”

Written by Forrest Moyer on June 18, 2020

Silas Manasses Grubb (1873-1938) was longtime pastor of Second Mennonite Church, Philadelphia, a congregation founded in 1894 as an outgrowth of First Mennonite, Philadelphia, where his father, N. B. Grubb, was pastor.

These were progressive congregations of the Eastern District of the General Conference Mennonite Church, and both father and son were educated and well-spoken. Both served as editors of The Mennonite, the denominational paper. Their congregations were filled with Mennonites who sought a modern city life rather than continuing to farm. In 1915, Second Mennonite Church had a membership of 190.

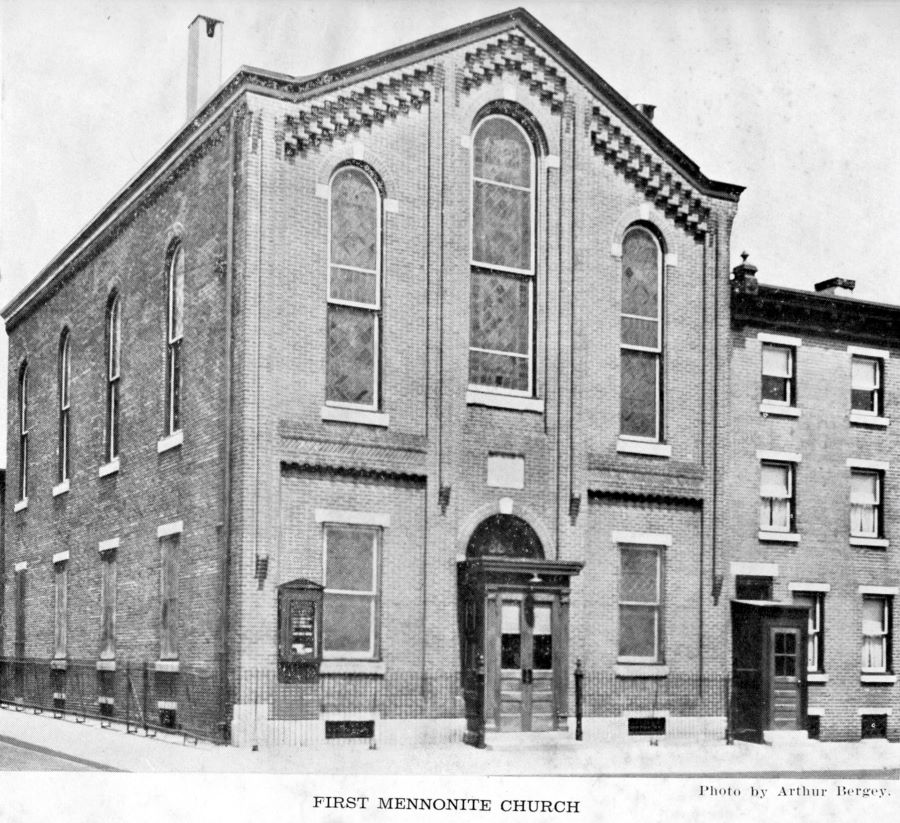

First Mennonite Church, Philadelphia, photographed by Arthur Bergey, circa 1940.

Second Mennonite Church, Philadelphia, photographed by Janette Amstutz, circa 2011.

The following essay by Silas Grubb was read at Eastern District Conference in 1913. It bears relevance for 21st-century Mennonites who live educated and affluent lives, and do not view themselves as separate from society. What does Mennonite faith mean in that (our) context? Why not identify simply as Christian?

I have excerpted the sections that most clearly articulate Grubb’s reasons for identifying as Mennonite, and added headings. His reasons, as I summarize them, were:

-Birth and environment

-Teaching versus emotion

-The peace position

-The Sermon on the Mount

-Non-swearing of oaths

-Flexible church government

-Separation of church and state

-Biblical literalism

-Simplicity

If you wish to read the entire essay in its original form, you can access it here: “Why I Am a Mennonite”.

Grubb’s approach was not perfect or entirely consistent and was shaped by his own time in history; but he set a good example by describing Mennonite identity in his context. What is it that leads one to take a Mennonite identity? Let’s see what Grubb said 100 years ago:

Birth and environment

…Environment is an influence which we, to be fair, must take into consideration when giving reasons for our connection with the type of Christianity of which we are a part. Environment accounts for most people’s church connections. Unless their relations have been disturbed by some peculiar providences, people are most likely to identify themselves with the church of their parents, or, at least, with that church most closely connected with the religious influences brought to bear upon childhood….

Denominationalism of every kind has to meet the charge that it is a species of cast[e] [i.e. social division by birth]…. Ours, we believe to be a reasonable system. It, at least, waits until the one who becomes identified with it [the Mennonite Church] knows and has the opportunity to act according to his knowledge [by choosing to be baptized]. That the caste idea has a strong influence with all classes of Christians, however, may be noticed by the disappointment, or even resentment, sometimes shown when changes of denominational affiliation occur….

Providence, when placing me in a Mennonite home, designed that I should meet the responsibilities and opportunities that the church of my parents brought before me. To have been born into a family whose ancestry has always been prominent and influential in the councils of the Mennonite church, whether it was the meeting at Dortrecht that gave us a formal written confession, or the one in Germantown, that, protesting against slavery, committed us to the recognition of the sacred rights of manhood, or at the gathering which led to the separation of 1847, that spake for the rights of private judgment in matters of faith, means to me that I have inherited a part in true maintenance of principles that are worth all the sacrifices they cost.

To bear the name of Mennonite means to be a representative in this generation of that church whose birth came by the fire of persecution and whose growth involved the dangers, privations and struggles of pilgrim bands in many lands….

Teaching versus emotion

I am a Mennonite because I believe in the doctrines of the Mennonite church. This belief, though a sacred heritage, is, after all, a thing that was born in me of conviction that came by a thoughtful perusal of the Word of God. There are types of Christianity that ignore the educational process commonly known as catechetical instruction and depend upon, or at least emphasize, the inspirational or the emotional methods by which men are brought to reject the world, the flesh and the devil and accept Christ. Very often the difference between the inspirational and the emotional are not defined or even clearly understood.

There are sometimes spiritual crises in some men’s lives that mark the spiritual birth of a new man with an undeniable distinctiveness. Such was the experience of Martin Luther when the sudden death of his companion by lightning led him to exclaim, “Henceforth I become a monk of the Order Augustine.” Such was the experience of Menno [Simons] when under the double sign of death he was to notice the martyrdom of Sicke Snyder and then to feel the pang of the sword in his own breast as his own brother [questionable] was led to execution for a part in the fanatical Anabaptist disorders. In both instances the subject rightly turned to the Word of God, and by diligent search found truth, solace and inspiration.

There are three things that must work a subject’s conversion: the Spirit of God working in him, the subject’s willingness to yield to the Spirit’s leading, and the guidance of the Word. Emotionalism too often leads one to suppose a peculiar mental experience to be all that is required in the making of a Christian and a fit subject for church fellowship. Unless the Word has its deep lasting influence in the experience of the subject and a process of sane reasoning backs up the suggestions that the emotions present, the Spirit has nothing to work upon and the conversion is apt to be only a fit of excitement.

There is a subtle danger in emotionalism. People run after it persuading themselves that its frequent appearance in them is an evidence of spiritual fruitfulness. “The fruit of the Spirit,” says Paul, “is love, joy, peace, long suffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, temperance…. If we live in the Spirit, let us also walk in the Spirit.” Gal. 5:22-25. Again, “The fruit of the Spirit is in all goodness and righteousness and truth.” Eph. 5:9….

The peace position

We owe a debt to our history. History imposes upon us a responsibility to posterity. The only way a cause is kept alive is through its living witnesses. Because of the faithful witness of the people of our church and those who have agreed with them in their peculiarities, we see today a growing sentiment toward universal peace. The last few years have marked the only serious attention the nations of the world have ever given to abolishing the hellish art of war. For centuries our people [Mennonites] have been regarded as harmless idle dreamers. Their consistent maintenance of peace principles sometimes gained sympathy for them, but too often contempt was the only thing given them. Today it must be admitted that they were far in advance of other Christians in this particular….

[Grubb’s political optimism may seem surprising, considering the Great War about to break out in Europe, but there was a robust international peace movement in the years preceding World War I: https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/pacifism.]

The Sermon on the Mount

Sometimes people get around the duties imposed upon the confessor of Christ in the Sermon on the Mount by explaining its precepts as ideals rather than laws. To attempt a literal obedience to these commands with them is visionary. This is a type of unbelief that would say: “The law of Christ won’t work out in practice.”

Non-swearing of oaths

To me the name of God is the most sacred syllable that my lips can utter. If I may honor Him in the use of His name it will only be as He directs. Now I am commanded not to take His name in vain. He forbids my taking an oath. All oaths, whether profane or judicial, are a plain violation of the words of Christ. “Swear not at all” means just what the words imply, notwithstanding all the sophistry brought to bear upon the subject. That the early Christians understood the Master clearly on this point, we may discover when James, many years later, repeats the sacred command.

The non-swearing of oaths which my church accepts as a law, dignifies the words of our Lord. It excludes the possibility of having His words mean the opposite of what plain language implies. When I read the confessions of the several historic churches, which teach that the oath is an institution divinely sanctioned, I thank God that I am not a part of those bodies who prefer to honor the Lord by commanding disobedience to His Word.

Flexible church government

Church polity was once a subject much made of and indeed it is today of vital importance to the existence of some Christian bodies, they going so far as to maintain that a true church, a legitimate ministry and a valid sacrament are only possible under their peculiar type of government. Space does not permit the discussion of the Episcopal, Presbyterian and Congregational types of church polity into which the various church governments are divided.

A church government, while it must have Scriptural sanction, should be flexible enough to rightly serve its purpose. The wise, saintly fathers of the church, call them bishops if you will, should have a governing influence. The councils of the elders, call them presbyteries if you care to, are often effective in their deliberations. The voice of the congregation, call it congregationalism if you want to, is the voice of the people of God whom the Spirit directs.

In my church I see a happy blending of the three systems. Do we not provide orders in the ministry according to the example of the apostolic church? Are not our conferences the bodies which guide the destiny of the church? And, after all, is not the voice of the congregation supreme? Who is there, be it bishop or presbytery, that can overrule a single congregation? I believe our polity to be flexible enough to be satisfactory in its working, yet rigid enough to conform to the New Testament type of Christian organization.

Separation of church and state

One of the first things that distinguished our church from other churches was its absolute separation from the state. This separation of church and state was advanced by Menno as a unique idea. It made the state the enemy of all who accepted the idea. With us today this is no more a new principle. The glorious history of our country proves that the church without political affiliations may be purer and more effective in its activities than the church which is a state institution. This Mennonite principle of separation of church and state has not outlived the necessity of its being emphasized….

Biblical literalism

We are sometimes sneeringly referred to as literalists. The ordinance of feet-washing, as practiced in some of our churches, the peace principles, the non-swearing of oaths, the Lord’s Supper as a memorial feast, the simplicity of our organization and the absence of a dogmatic literature among us may well warrant the bearing of the name literalist, but what of it? Are we not to take the Bible for what it expresses in plain language?

Right here let me express the opinion that the Bible is safer in the hands of our people, in our pulpits and in our schools because our people accept inspiration to mean that the Bible is the Word of God and therefore cannot be a development from cleverly blended myths or hazy documents, whose existence in original form must be assumed. Because it is from Him, miracles are not figures of speech and our Christ is Divine.

With a history such as ours and an independence of thought such as our people have always shown, I cannot imagine the possibility of our people ever surrendering the Bible to the tender mercies of destructive critics and one-sided philological experts.

[Coming from a tradition of simple obedience and biblical literalism, many Mennonites hold a doctrine of biblical inerrancy, as Grubb did. Later in the 20th century, this became a divisive issue, and half of the Eastern District Conference (including Second Mennonite Church, Philadelphia) separated from the national denomination and founded the Alliance of Mennonite Evangelical Congregations.]

Simplicity

The simplicity with which Mennoniteism has always been distinguished makes us feel that we have something in our faith that appeals to the plain man. There may be High-church Episcopalians or High-church Lutherans, but High-church Mennoniteism would be an absurdity. The tendency toward this sort of thing is decidedly marked in our day. Our mission is to preserve a faith such as the slaves and refugees in the sandpits and quarries of Rome could practice in primitive times when velvet vestments, bejeweled crosses, gilded altars and shining candles were out of the question, and prayer, exhortation and singing of hymns were the order of service.

[Some would say that Grubb’s church in Philadelphia was quite fancy or “high”; but from his perspective their style of worship was plain compared to city churches of other denominations.]

As a Mennonite I have a part, a responsibility, in ministering to the needs of the miserable, in testifying for Christ before the world and in carrying the gospel to the heathen. These duties I cannot shirk. I must undertake to engage them in company with those with whom I can best work effectively — those whose ideas and ideals are nearest my own. Therefore I am a Mennonite.

Silas died in 1938, after many years of ministry in Philadelphia. His obituary was published in The Mennonite, Feb. 15, 1938:

Rev. S. M. Grubb, D.D., the former editor of The Mennonite, official publication of the General Conference of Mennonites of North America, passed away quite suddenly and unexpectedly at his home in Philadelphia, Pa., Sunday morning, Feb. 6. Widely known throughout the conference, Dr. Grubb had an active life until his death, which came at the age of 64 years. Funeral services were held in the Mennonite church at Philadelphia, conducted by Rev. J. J. Plenart and Rev. Freeman Swartz. Among those surviving are his wife, a son, a daughter-in-law and his aged father, Rev. N. B. Grubb, 88 years old.