Camp experiences of David H. Gehman, World War I

Written by Forrest Moyer on February 6, 2019

David Gehman (1894-1969) grew up near Bally, Pennsylvania. His father was Enos Gehman, whose teenage journal of a trip to Philadelphia was published on this blog.

David’s memoir of his experiences as a conscientious objector during World War I is found in the J.C. Clemens Papers at the MHC (Hist. Mss. 3). It was first published in the MHEP Newsletter in 1983. Gehman’s accompanying note was not included, but an excerpt reveals how he came to record his memories and eventually send them to the Franconia Mennonite Historical Society:

Jan 26, 1955

Dear Bro. J. C. Clemens,

…I thought maybe this would be something for our historical library in Souderton. I don’t know why I am sending this to you, only I know you lived during this time and I thought maybe you would be interested to read this. Goshen College asked me for my camp experience about 8 years ago, so I gave them some things, and I told them if they would like to have it more complete, I would wait till [daughter] Anna Mary was home as she was in school at Harrisonburg [Virginia] at this time. They told me that they would like to have it complete, so I asked Anna Mary to write and I dictated. Then Anna Mary’s teacher asked the class if anyone in the class had any records at home of historical value, so she told about this camp experience, and when she brought this to school the Principal made the whole class read this, so I thought that this may have some historical value after all. So you can keep this as I have a copy of this….

[headings added]

Drafted

It was September 6, 1918 that I was drafted for military service in the U. S. army. Since I was the youngest of four boys, I was probably the least one thought of to be drafted. In those days, there was very little teaching on nonresistance. My brothers attended a special nonresistance program at one of our churches, but I was not asked to go along as traveling was not as convenient as it is now. I did not have any chance to hear a special nonresistance service then as I would have liked to. My brothers received helpful Scripture references which they gave me to take along. This helped me out many times but it would have been much more beneficial if I could have attended the meeting myself.

My father [Enos S. Gehman] was quite feeble at the time. He had diabetes and diabetic cataract. He was blind for a whole year then was operated on and regained sight for one year. When I left for the station, my father stood beside the living room table with his head against mine and saying that he couldn’t come to see me anymore, but that I could come to see him, meaning this would cause his death. Ever since this, whenever I think of him, I can visualize him standing in that position just as I left. I never saw him alive since that time.

Then I left for Birdsboro with my brothers. There was a huge crowd at the station which was a sight I shall never forget. There was crying, praying, confusion, and also laughing by those who wanted to break the monotony. There were many girls lifted up to the train windows to give one more kiss to their lovers. After the train had started, a comedian came through trying to cheer us up but there was no laughing whatsoever.

After reaching Camp Dix, New Jersey, we received two hours of sleep yet that night, but I know many did not sleep at all.

No provision for objectors

There were no provisions for objectors. They were drafted into the regular army, so I was among the soldiers. Very soon I went to the Sargent stating that I was an objector and that I could not take the uniform. I had tried to see him privately, but when he heard this he put up his arms and yelled at the top of his voice –“Hey boys, here’s a yellow streak.” At this time I was called many vulgar names. I was under this strain for about three weeks. My trial had begun!

…He put up his arms and yelled at the top of his voice — “Hey boys, here’s a yellow streak.”

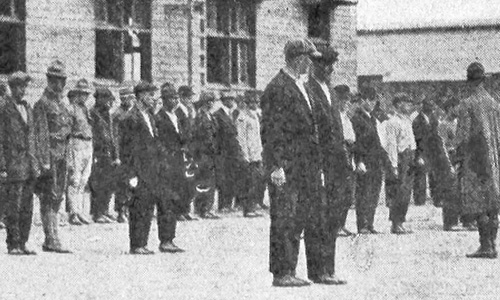

Soon the test of the uniform came. We were all lined up to be uniformed. We had to stand for quite some time, and as I felt weak I stooped down and prayed. Finally the Sargent came up the line and asked if there were any yellow streaks in this crowd. I stepped out. Then he asked if there were any more, so another stepped out whose preacher told the Sargent he could do some things for the army. Because of this he was roughly ordered back into line. Following him another stepped out who was an International Bible Student of America. He was asked what he could do and he answered that he would do service outside the military establishment but couldn’t accept the uniform. So we two faced the crowd of about three or four hundred men. The Sargent started to make fun of us there in public. Nothing seemed too vile for him to say. I have never heard such filthy ridicules before or since then. Many others followed him in ridiculing us. We two faced the crowd looking upwardly into the sky. Finally the others were sent to be uniformed, and we were sent to our tents.

Now the punishment came for objecting the uniform. We had to carry large garbage cans filled with kitchen slop for the distance of about four city blocks for one and a half days. As we passed other soldiers they made fun of us in many ways. Toward the end our hands were so sore we could hardly carry them anymore.

This happened on a Saturday and Sunday forenoon, therefore the other men weren’t busy and could ridicule us. On Sunday the captain asked us to come to his office to sign up as conscientious objectors. Then we were left alone for the rest of that day.

We were then asked to dig post holes around a hole with an embankment, and these post holes were halfway up the embankment. This hole was used for disposal of kitchen slops. Because it was raining, the sandy ground was slippery, therefore we had to dig on our knees while others stood around and laughed at us. They even threatened to bury us alive in the holes we made. At another time a few soldiers were making fists at us and told us if they had us out back they would love to kill us. We just listened and said nothing.

Protection from angry mobs

Another time two school teachers asked to speak with me. This was my hardest test because they had much education and used sweet methods in endeavoring to persuade me. They said fighting was essential in this war. I told them all about my father and the things he told me. Then they seemed to understand. One time the captain asked me to accompany him to his tent. I picked weeds and shined his leather leggings to pass the time away. His main object of this was to protect me from the angry mobs, I believe.

It was around this time I received a letter from home, containing the dreadful news that my father was dead. The Sargent told me if I would accept the uniform he would let me go home the next day for my father’s funeral. I told him to let come what will, I would never accept the uniform. I also told him that if I would go home with a uniform and my father would see me, it would break his heart. I related to him the story of how my father encouraged me to be faithful to the Scriptures. Then he walked away without saying a word.

I related to him the story of how my father encouraged me to be faithful to the Scriptures.

Around this period about half the uniformed men who stood in line when we were ridiculed came to us privately and told us tapping our backs that we stood for the right. Many said they wished they could have taken the stand that we did. They admitted we were right and they were wrong. This really gave us courage.

Having only received a letter stating father’s death, I now received a funeral notice. This convinced them that my father had died after they doubted me. The Sargent arranged my pass to go home. This took one and a half days to get through all the “red tape” which were examinations as we had an epidemic of influenza. Many men died of this.

They reserved a grave for me

When I reached home, I was sad and yet glad my father was relieved of his misery. He looked so calm, and I knew if he knew all I went through he wouldn’t have been so calm. On the day of his funeral I was sick with influenza and I could not go. I found out afterward that they had a place for a grave reserved for me beside my father thinking I would likely follow him. The good Lord saw fit for me to live of which I’m grateful!! I had to stay ten days longer than what my pass permitted because of my illness. We received a second notice from the army headquarters at Camp Dix stating that I had to return immediately regardless of my condition. So I left at once.

When I came there at the Camp Dix station, I had to walk for three miles to my tent. This was very hard because I was so weak. Then I was sent at once to the doctor to see if I really had influenza.

Later I was transferred to the objectors camp about one and a half miles back. Here I carried my heavy suitcase, and the orderly had to go with me. I told him I could hardly carry it and walk, so he said I should just carry it until we were out of sight. Then he took it for me. At the square there was a fire plug with posts around it. I could hardly wait to get from one to the next to rest awhile. I finally got to the other objectors which were eight in number, but there were no Mennonites other than me at this time. Here we all lived in two tents beside the woods alone, and here is where I was restored to good health again.

Objecting companions

One of the objectors called himself a “Primitive Christian.” His only reason for not fighting was that it was wrong to kill. He didn’t even believe it was okay to kill a mouse, bug, fly or anything. He would often tell me to take the mice, which were in our breadbox, out in the woods and let it run. I took them out, but I killed them too. He did not believe the Bible, claiming that his books were much more ancient.

Another objector who was converted in the Salvation Army tent had scars on his face from beer bottle fights. This man started our prayer meetings. Whenever we had prayer meeting, the Primitive Christian walked out. He was offered the rifle but objected. This put him in the guard house as prisoner because he had no Biblical reason for objecting. He was transferred to us for awhile, and they offered him the rifle again, but he refused. Again he was sent to the guard house as prisoner. He went through this circle many times.

Another objector called himself a “common sense” man. All he said was that common sense tells a person its wrong to kill.

The I.B.S.A. [International Bible Student] fellow had been in this group when I came. As his stand was he could do something outside the military without a uniform, he was transferred to the Post Office and worked there.

Two objectors were Christadelphians. They had Biblical reasons for objecting. Before we went to New York two Mennonites were transferred to our group.

Our group included one negro (half-negro). His name was Skeeter. One day an officer told Skeeter to pick up some paper showing his stripes which indicated his position. He told him, “You know who I am. Pick up that paper!” Skeeter replied, “He that lacketh in the least is guilty of it all.” He did not obey military commands. He was very firm on the Scriptures. He was a personal encourager to me and also the group. Sometimes he would speak to us and even the officers would listen. A few times he would sing negro songs while sitting on his cot in his humble position. Of the most impressive was the song “Shadrack, Meshack, and Abednego.” As he sang this, he held up his three fingers and said, “there were three in the fiery furnace, but when the king looked in there were four.” Then he held up four fingers. This he did in such a cheerful way giving us all courage. He often said boldly, “If I were put in prison, the walls would surely fall down.” This shows his outstanding faith.

The other objector was a Norwegian who would read three languages. He was taken in as a “draft dodger” because he didn’t believe it right to register for military service. This man I considered faithful. He was not a citizen of the U.S. because he wanted to be a citizen of Heaven. He believed it was wrong to take citizenship papers.

During my stay here with the objectors I was visited by Brethren Joseph Ruth, Wilson Moyer, Warren Moyer, and Jacob Moyer who is now Bishop.

Examination in court

Our group was sent to New York to be examined all except the primitive Christian as he was judged unworthy to go along by the officials. When we reached New York, we were tried by Judge Mack and Major Stone who later became Chief Justice. As we were waiting to be called in by the judge, our officers came out of the judge’s room and asked us where it was found in the Bible about Christ making a scourge out of ropes to drive them out of the temple. Immediately Skeeter, the Negro Brother, pulled out his pocket Bible which was worn hard. It opened at the right passage — John 2:15. Then the officer took the Bible in to the Judge. After this we were all tried separately. My first question was about my name. The second was if I was willing to accept a farm furlough. I said “Yes.” Then he asked if I knew they were hard and dangerous places. I said “Yes, sir.” Then he excused me. This told the Judge I was not afraid of persecution for conscience sake.

When the negro was asked “What can you do for us?” he answered “Nothing whatsoever.” Then the Judge said, “Man, it will go hard for you.” The Negro Brother said, “All flesh is as grass that withereth.” The Judge said, “Excused.” I do not know the other questions the other objectors were asked, except the “common sense” man. His reason for objecting seemed to get him through all right. On the way back to Camp Dix one of the group asked our officer what the negro was asked in the Judge’s room. This is how we found it out. Our Captain told us that he would probably be discharged for insanity because he preached so much.

How objectors were disposed of

After reaching Camp Dix many objectors came back from farm furloughs to be sent to France for reconstruction work. Among these were two Socialists. One of them told of his experience in objecting to the uniform. I cannot give this in detail but the outstanding fact was that he was court martialed to be shot the following morning at sunrise because he was judged by the officers as an unfaithful objector. He, believing this to be true, jumped on a taxi and went home to bid his parents farewell. Upon his return, he found his sentence of death printed on the bulletin board. The president had not signed it yet. That was the end of that.

On the day we were discharged, one of the boys passed the guard house where the primitive Christian still was held as prisoner. He told him we were going home and offered him a Bible. His heart was heavy and sad, and he said, “Yes, please.” We had to give it without the guard seeing it as it was against Army regulations to hand anything to a prisoner.

We asked a group of colored people who passed us when we were waiting outside the mustering-out office, where our friend Skeeter was. They said, “Oh, he went home long already.” He had been transferred to the colored Battalion after coming back from New York. From there he may have been discharged because of preaching.

Now this was the day we were discharged. I had to accept my pay in order to receive a discharge, but I was requested by our church to send it back as a donation to the government.

I had to accept my pay in order to receive a discharge, but I was requested by our church to send it back as a donation to the government.

However sad this experience may be, it is extremely valuable to me in steadfastness. I often realize that it was only by the protection of the Almighty God that I was brought home safely.

A.M.G./D.G.

The exhibit Voices of Conscience: Peace Witness in the Great War, which highlights the experience and witness of objectors and activists during World War I, is on display at the Mennonite Heritage Center through this coming weekend. It will close on Sunday, February 10, with a program at 2:00 p.m. by Anne Yoder, archivist of the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, on “Women Pacifists and Their Response to World War I”. The exhibit will be open for viewing after the program.