Our Immigrant Heritage: Funk

Written by Forrest Moyer on August 11, 2017

This series of posts highlights families descended from 18th-century Mennonite immigrants to eastern Pennsylvania, in connection with the MHC’s exhibit Opportunity & Conscience: Mennonite Immigration to Pennsylvania, on display through March 31, 2018. The stories reflect the enrichment brought to communities over centuries by the descendants of immigrants.

Henry Funk, miller and author

The Funk story is one of strong influence, within and beyond the Mennonite community, from immigrant Henry — the first American Mennonite author — to descendants Annie and John F. Funk, two well-known Mennonite characters of the early 20th century.

Henry Funk (d. 1760) was one of the first settlers in what became Franconia Township, buying land along the Indian Creek in 1718. A man of deep Anabaptist roots in Switzerland, he was a church leader, helping to organize the Salford and Franconia Mennonite congregations. He served as their first resident bishop, alongside his deacon brother-in-law Christian Moyer.

Apparently Funk and Moyer had conflict, though we do not know why. Funks’ son, Christian, wrote at the end of his life — in a memoir entitled Mirror for All Mankind — that the bishop who succeeded Funk, Isaac Kolb, stated to a large gathering of ministers (probably the semiannual conference) that he didn’t feel able to work with Moyer because of “all the trouble that Moyer made for old [Henry] Funk”. Christian didn’t elaborate on what the trouble was, but against Moyer’s wish (and perhaps others in the congregation), Christian himself was chosen by lot to become bishop at Franconia; after which Kolb was satisfied and peace continued for a decade until the “Funkite Schism” of 1778-79 (see below).

Henry Funk was likely an outspoken and opinionated leader, as he wrote two books of theology at a time when most Mennonites (like deacon Moyer perhaps) were focused on clearing and cultivating their own farms and finding land for their children. In addition to Spiegel der Tauffe (Mirror of Baptism) (1744), Funk wrote a theological work entitled Restitution that was published posthumously in 1763 by his children. At 308 pages, it was the largest book written by an American Mennonite for many years after. He also, with minister Dielman Kolb, proofread the massive Martyrer Spiegel (Martyrs’ Mirror) when it was translated into German and printed at Ephrata in the 1740s.

Henry Funk’s writings. On the left is the first Mennonite book written in America, Ein Spiegel der Tauffe mit Geist, mit Wasser, und mit Blut [A Mirror of Baptism with Spirit, with Water, and with Blood], printed by Christopher Sower at Germantown in 1744. As a member of the Church of the Brethren, Sower would not put his name on the title page because of the book’s argument against immersion baptism. This copy is in the collection of the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society.

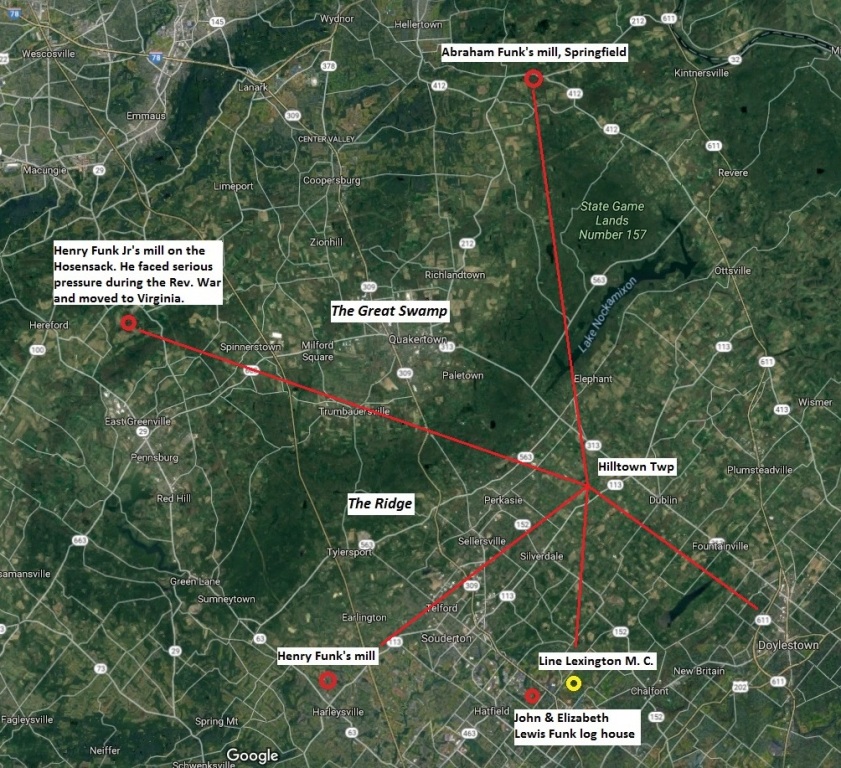

In addition to reading and writing, which he likely did by candlelight in the evening, Henry Funk operated a grist mill that stands today on Mill Road, near Harleysville (map). Across the street is an old house believed to be built in part by the immigrant.

18th-century walls of the Henry Funk house on Mill Road, Franconia Township.

From Franconia, Funk’s sons moved to Hilltown Township, where eldest son John settled and his descendants spread throughout Bucks County. Son Henry (on whose land the Blooming Glen Mennonite meetinghouse was built) moved again, northwest over the Ridge past heavily-settled Great Swamp to the tight valley of the Hosensack Creek in what is today Lower Milford Township, Lehigh County. There he operated a mill at the corner of Schultz Bridge and Buhman Roads (map). Eventually he moved from there, south to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia in 1786. Son Abraham bought land and a mill in Springfield Township, Bucks County, where Funk’s Mill Road meets Rt. 212 at Cook’s Creek (map). Son Christian remained on his father’s farm in Franconia.

There was another family of Funk’s who settled in Hatfield Township in the 1740s. Martin Funk (d. 1765) was likely a brother of bishop Henry Funk. His son John (who married a Welsh Baptist woman, Elizabeth Lewis) became one of the first ministers in the Line Lexington Mennonite Church. John and Elizabeth’s log house along Orvilla Road, probably built in the 1760s, is today just a shell and set for demolition. Neighbors have been campaigning for its preservation.

The Funkite Schism

Christian Funk (1731-1811), who followed in his father’s footsteps as miller and bishop at Franconia, became the central figure in a schism that divided local Mennonites during the War for Independence. Those who sided with Funk were called “Funkites” by historians and probably also by people of their own day. The bad feeling that divided congregations and families stretched well into the 19th century.

The critical issue was Funk’s willingness to accept Mennonite support for the American Revolution. In 1777, long before it could be known whether Britain or the United States would win the war, Pennsylvania passed a Test Act, requiring all citizens to renounce the king and pledge loyalty to the new “free and independent” Commonwealth of Pennsylvania or lose privileges of citizenship. This created an ethical and security crisis for Mennonites, and undoubtedly led to heightened emotions.

Most Mennonites refused to support the Revolutionary cause, feeling it immoral to reverse their word of loyalty to the king or to take up arms (i.e., support an army) in rebellion. Christian Funk, however, felt that obedience to Pennsylvania was sufficient, and he allowed church members to pay taxes to support the Continental Army. Because of this, he was “banned” (excommunicated) by his fellow bishops, the congregation at Franconia, and his uncle, old deacon Christian Moyer. (It should be noted that we know this story only from the writing of Funk himself; the other side left no record.)

Christel (Christian) Funk’s memoir, Spiegel fuer alle Menschen [Mirror for all Mankind]. Mennonite Heritage Center Collection.

Resentment and anger stymied any attempt at reconciliation until 1804 when two bishops who had been ordained since the division — Jacob Gross and David Ruth — attempted to make peace with Funk and recommended his restoration to the church. They required, however, that Funk admit his error during the war. This Funk refused, feeling that he had worked in good conscience.

Two years later, Funk approached the bishops again for reconciliation, and this time they seemed willing to accept him without confession of wrongdoing. Gross said, “Funk, we have nothing against your address; we are satisfied with it. But because the ten ministers [who banned you] have died, we don’t like to say that the ban is [was] altogether just, and we also don’t like to say that the ban is altogether unjust. We want to leave it to the deceased ministers, because they maintained church discipline as they understood it, and we maintain discipline as we understand it, and we want to let by-gones be by-gones and make peace. But we want to present it to your Indian Field [Franconia] congregation and then you must accept what they require of you.” (Funk quoting Gross in Mirror for All Mankind, translated by Daniel Reinford)

When Funk’s restoration was recommended at Franconia, the laymen were less receptive: 118 insisted that Funk admit error; only 45 would accept peace without confession. Further, they would not recognize the ordination of Funk’s co-ministers, his son John Funk and son-in-law John Detweiler. Those voting were Funk’s close neighbors and family members; they had lived with this division for three decades and felt it deeply. They wanted Funk to request forgiveness.

Clearly, there was still too much pain and misunderstanding to effect a true peace. Rather than admit error, Funk withdrew (he passed away a few years later), and the Funkite Church continued to worship separately until the 1840s, when only old people could remember the war and its troubles and the Funkites filtered back into the Mennonite Church, Church of the Brethren, Brethren in Christ, or other local churches.

Drawing (less than accurate) by local historian John D. Souder of the Funkite Meetinghouse in Franconia (Delp’s Meetinghouse), located on Indian Creek Road near Funk’s mill. Souder noted that the last communion was held here in 1851. Image courtesy of Joan Hallman.

Joseph Funk and the Harmonia Sacra

Christian Funk’s nephew Joseph (1778-1862) made a contribution to harmonious community that stretched beyond the Mennonite world through the publishing work of his grandsons. He was born in Pennsylvania but moved at a young age with his parents to Virginia, where he lived the rest of his life. He became an enthusiast and teacher of harmony singing. In church (at least in the Mennonite church) hymns were sung in the slow unison style of the 16th century. Learning to sing English-language hymns to upbeat four-part tunes was an exciting venture into the arts. Compare these recordings of old-fashioned Mennonite singing and the type of four-part singing that Funk taught (which has been promoted in the mainstream Mennonite Church).

Joseph Funk published shape-note harmony singing books, the most popular of which was A Compilation of Genuine Church Music (1832), later published under the title Harmonia Sacra. The book has seen many editions, and continues to be used, most notably for a large singing at Weavers Mennonite Church, Harrisonburg, Virginia each New Year’s Day. Additional singings are held throughout the year.

Just as his grandfather was the first Mennonite author in America, Joseph Funk established the first Mennonite press in this country in 1847. It would eventually become the Ruebush-Kieffer Company (Ruebush was Funk’s grandson-in-law, and Kieffer a grandson). The Encyclopedia of American Gospel Music notes that “[Funk’s] sales and influence eventually extended far beyond the [Shenandoah] valley. Under the leadership of his grandson, Aldine S. Kieffer, who adhered to many of his grandfather’s precepts, the family business became the clear leader in the growth and dissemination of shape-note and Southern gospel music.” A. J. Fretz, genealogist of the Funk family, wrote that because of Funk’s musical work, “thousands unknown to him, personally, will cherish his memory as the instrument through whom their lives have been cheered, and their devotional hours brightened by the songs of praise which were brought to them through his labors.”

But Joseph was not completely free of old family fights. He translated and published his grandfather’s anti-immersion Mirror of Baptism in English in 1851. When Brethren elder John Kline wrote a scathing review, Joseph hit back with The Reviewer Reviewed in 1857: “…As this review was not written in the spirit of an humble, self-denying Christian, as it should have been; but to the contrary, in a haughty, arrogant, and assuming spirit…and whereas he lays things to the charge of the author and translator which are really not so, but are perverted from their proper meaning, therefore it was thought proper by the translator, to reply to it, and rescue the honest design and meaning of the author…from being ridiculed in a scornful and unreasonable manner, and misconstrued by its ungenerous reviewer.”

To be fair, Kline had suggested that Henry and Joseph Funk were willfully deceiving readers about the meaning of Scripture. The irony is that both Funk and Kline were well-loved and respected in their communities. Their insults and arguing highlight the competition that existed between Mennonites and Brethren in early America as many Mennonites converted and were re-baptized into the Brethren faith.

Illustration of a Brethren elder with full beard (a Brethren requirement) baptizing a convert by “trine immersion”, three times forward under the water in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Illustration from Peter Nead’s Theology, circa 1830. Isaac Clarence Kulp Collection.

John and Annie

John F. Funk (1835-1930), who picked up Mennonite publishing where Joseph Funk left off, has been called “the outstanding leader of the Mennonite Church (MC) in the 19th century” (Harold Bender, The Mennonite Encyclopedia). He was born and raised in Hilltown Township, Bucks County, but moved to Chicago, Illinois, where he published the periodical Herald of Truth (in English and German) for nationwide distribution to the Mennonite community, beginning in 1864. This later became the Gospel Herald, the official organ of the “Old” Mennonite Church.

John was ordained a minister in 1865, and a bishop much later in 1892, but during the period of 1870-1900, he had probably greater influence on the Mennonite Church than any other person, through his publishing work and assistance of Russian Mennonite immigrants settling in the western U.S. and Canada. Early influenced by D. L. Moody in Chicago, Funk (with others such as John S. Coffman) led the Mennonite Church (MC) to a new evangelical emphasis, balanced with a respect for traditionalism, that became its defining character in the 20th century (Bender, Mennonite Encyclopedia).

As a powerful outspoken figure, however, he could not escape a fate similar to that of Christian Funk in the Revolutionary Era. In 1902, Funk’s service as bishop was suspended because of factions that had developed in his congregation at Elkhart, Indiana. Though the suspension was stated as temporary until he could regain the trust of ministers, deacons and members of his district, he was never reinstated as bishop.

Funk’s grandchildren wrote, in a 1964 biography, that it was perhaps best he was not reinstated: “Had this been done, a schism would almost certainly have resulted…. Funk had recorded his judgment that it would be better to have a split in the church, so that the faithful portion, without the disobedient ones, could witness clearly to the doctrines and discipline of the Mennonite Church. When it was all over he simply said: ‘I did the best I could and I would do it again. If I had been wrong, I am sorry.’ Funk steadfastly refused to confess any error, and in the end he was finally recognized as being in good standing in the church upon the recommendation of Deacon George L. Bender.” (Bless the Lord, O My Soul, p. 184)

On the less contentious “New” Mennonite (GCMC) side of things, mention should be made of Annie C. Funk (1874-1912), a descendant of Henry Funk, miller at Hosensack. She was raised in the Hereford Mennonite congregation. Like John F. Funk, she was influenced by D. L. Moody, attending his Northfield (Mass.) Training School before going as a missionary to India in 1906. She founded a girls’ school at Jangjir and likely would have had a long career in ministry, but her life was cut short as she perished on the sinking Titanic while attempting to return home for a visit in 1912. It was reported that she gave her place in a lifeboat to a mother with children. Watch a video about Annie’s life and work here.

Portraits of John F. Funk and Annie C. Funk.

Sources on the Funk family

Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Numerous articles on the Funk/Funck family. http://gameo.org/

Fretz, A. J. A Brief History of Bishop Henry Funck and Other Funk Pioneers, and A Complete Genealogical Family Register. Elkhart, IN: Mennonite Publishing Co. 1899. Online at https://archive.org/details/briefhistoryofbi01fret

Funk, Christel [Christian]. Mirror for All Mankind. 1809. Translated by Daniel J. Reinford. Available in the MHC library. Another translation, by J. C. Wenger, was published in Mennonite Quarterly Review (Jan 1985).

Ruth, John L. ‘Twas Seeding Time: A Mennonite View of The American Revolution. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press. 1976.

Shearon, Stephen. “Funk, Joseph.” Encyclopedia of American Gospel Music. New York: Routledge, 2005, 134-135.

Wenger, John C. History of the Mennonites of the Franconia Conference. Telford, PA: Franconia Mennonite Historical Society. 1937.

Sources on John F. Funk

Bender, Harold S. “Funk, John Fretz (1835-1930).” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Web. 9 Aug 2017. http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Funk,_John_Fretz_(1835-1930)

Gates, Helen Kolb et al. Bless the Lord, O My Soul: A Biography of John Fretz Funk [by his grandchildren]. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press. 1964.

Maust, Ted. “‘Union with such as we might perhaps otherwise never know’: John F. Funk and the Herald of Truth, 1854-1864.” Pennsylvania Mennonite Heritage 38:2 (Apr 2015), 40-54.

John F. Funk Papers in the Mennonite Church USA Archives: http://mac.libraryhost.com/?p=collections/controlcard&id=184