Brunk Revivals: a watershed moment for local Mennonites

Written by Forrest Moyer on July 27, 2021

This essay by Paul Lederach was published in the MHEP Quarterly in 2001. He recalls an event that had far-reaching effects on the practice of local Mennonites in regard to evangelism, salvation, confession/forgiveness, and corporate/individual faith.

When I travel west from Souderton to Harleysville on Pennsylvania Route 113 and stop at the traffic light at Godshall Road – a CVS on the northwest corner and many houses on the northeast corner – I can scarcely remember when the northeast corner was a wide, level, seventeen-acre field. In 1951, evangelist George R. Brunk II and his brother Lawrence came with their vans, trucks, equipment, mobile homes and tents to conduct a “mass revival” on that field on the outskirts of Franconia village.

Before George and Lawrence came to Franconia they led a revival in Lancaster City, Pennsylvania. Aware of the Spirit’s movement there, the bishops of Franconia Mennonite Conference unanimously invited the Brunks to the Souderton area. Upon their acceptance the Young People’s Activity Committee was given responsibility to make arrangements. Many committees were formed, such as one for arranging facilities, one to provide and be in charge of equipment, another for parking and arranging with police for traffic control, to name a few. The revivals became a community project. When the Brunks arrived Monday afternoon, July 23, a host of men gathered to erect the tent, place chairs, electrify tents and equipment.

Thousands attended each evening

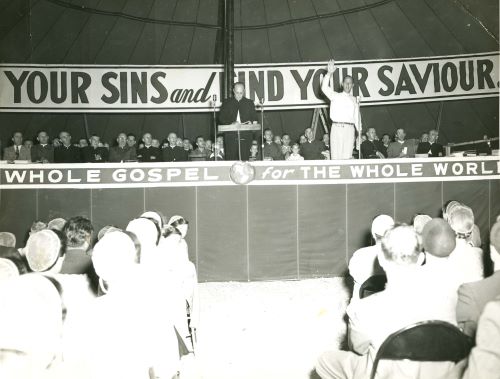

From the beginning the revival had the full support of the bishops, most pastors and deacons. The meetings began July 29 and continued through September 3, 1951. The meetings did not begin with low attendance and then build as time went by. The first night an estimated 4,000 persons attended, so also Monday and Tuesday following. Then an overflow tent was erected seating 1,000 more. Attendance soared to 10,000 or 12,000 on weekends. By the end of the campaign there were three tents: the first 70′ x 188′ held 3,000, the overflow another 1,000. A third tent was erected the Thursday before the final meeting September 3. It was 100′ longer than the first and seated 6,000 persons! In addition to the tents and other mobile equipment the rest of the field was used to park row after row of automobiles belonging to those attending.

Before the meeting began, there was an accident. Friday, George was nearly electrocuted. As a result of the accident, George was unable to preach the first evening. Bishop John E. Lapp preached the first sermon of the campaign. Thereafter George preached with his arm bound close to his body. The near tragedy seemed to bring the community together as believers prayed fervently for George and the meetings.

During the days of the revival, there seemed to be round the clock activity – from dawn till late at night. Each day there was a prayer meeting beginning at 6:00 a.m. Another prayer group gathered each evening at 6:45 p.m. During the day persons were coming and going – to meet with persons accompanying the evangelists, to service equipment, and to meet with George and Lawrence for fellowship and counsel.

No singing by individuals or groups

The services began at 7:30 p.m. each evening. First was a lengthy period of acapella singing of hymns and gospel songs. There was no special music, such as solos or quartets, since this was still forbidden in some congregations and was frowned upon in the Conference Discipline. When everyone joined in singing, this too was a unifying aspect of the revival experience. Lawrence Brunk led the singing.

The services were more informal and less structured than many were accustomed to. Ministers in attendance sat on the platform facing the audience in order “to make more seats available” in the tent!

After scripture reading, prayer, testimonies, and more singing, George began to preach. His sermons were not short – most averaged an hour. Sermons were topical rather than exegetical. His manner of preaching was appreciated by most. It was criticized by those who felt the sermons were at times judgmental and sarcastic. Nevertheless the Gospel was preached.

Click here for a sample of Brunk preaching in 1952.

Embracing evangelical-style confession

George concluded his sermons with an invitation. They were neither prolonged nor tedious. The “Gospel Net” was cast. Men, women, youth, and children were invited to accept Christ, to confess sin, to make things right, to seek peace. Each evening many persons responded and went to a prayer room. There ministers and lay persons helped the responders find a new relationship with Christ.

After the invitation and benediction, the service continued with a “Testimony Service”. Persons who dedicated their lives and found peace and felt blessed by the Spirit were invited to the platform to share their experience. It was stressed again and again, “If you have no testimony, you need a confession!”

What were the results of these meetings? Statistics tell an incomplete story. It was estimated that 850 persons responded to the invitation. Of these 250 were first time confessions of faith. The number of persons who recommitted their lives to Christ and the church, the number of reconciliations, restitutions, and confessions of sin will never be known.

The meetings had many spin-off results. Congregations became more spiritually alive. Singing took on new meaning and vigor. Worship tended to be less formal with new opportunities for sharing testimonies, concerns, and confessions. Pastors developed new awareness of the importance of pastoral care. Cards signed by persons who responded to invitations were given to pastors for follow up. This provided new opportunities for visitation and counseling.

Young people inspired by the meetings initiated prayer and Bible study meetings. The “Franconia Cowboys”, a group of men converted in the meetings began to hold weekly meetings at the Perkiomenville Mennonite Church. They invited Bishop Lapp to one of their meetings. Later he bore testimony to the remarkable changes in their lives.

It is to the credit of bishops and pastors that confessions of sin were handled in sensitive and discrete ways. They worked privately helping persons find forgiveness and peace. Securing permission from each person, his/her name was shared with his/ her congregation as one who received help. They were given the opportunity to share their experience with the congregation. Specific sins were not announced. The old system of excommunication followed by restoration was by-passed in favor of kinder, gentler, ways of dealing with personal failure.

Results in congregations and conference

In many congregations there were profound moments of revival. One Sunday in August at Franconia Mennonite Church an invitation was given to renew dedication to Christ and to give testimony. Over 130 persons responded.

A similar invitation was given at Blooming Glen Mennonite Church on August 26, 1951. I remember this well since I was pastor there at that time. There was a moving outpouring of the Spirit as sins were confessed, as persons embraced one another asking forgiveness and seeking reconciliation. Approximately 85 persons publicly responded. In love persons put away conflicts and hostilities that had divided the congregation for a long time. In response to a call for reconsecration, the entire congregation (with a few exceptions) stood together. There were two conversions in that service. The morning worship service did not conclude until 1 p.m.

This was a watershed in the life of the Blooming Glen congregation. New unity was experienced especially in the call of long term pastoral leadership. The congregation voted in October to call David F. Derstine as pastor, with a nearly unanimous vote.

Mission News, the paper of the Franconia Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities, devoted its September 1951 issue to the revival. Editor Elmer Kolb secured written testimonies from many persons from congregations in the Conference.

Franconia Conference in its fall session, October 4, 1951, adopted this:

Praise to God for revival blessings experienced in the recent past. We humbly confess our failures as ordained men in that so many of our members have carried burdens of sin and doubts in their hearts, some of them for years. We dedicate ourselves anew to be more faithful in fulfilling our calling as ordained men in providing for:

(1) The strengthening of our homes.

(2) Better nurturing of our young people, especially in their social and devotional life, and in fitting them for Christian service.

(3) More opportunities in our congregations for revivals, confessions, and testimonies.

(4) Definite preaching on all sin, including the awful social sins, and more definite positive teaching on Christian assurance.

(5) More effective and thorough pastoral work in the homes of our people.

(6) More careful use of our own time in Bible study, prayer and sermon preparation.

Treatment by historians

Beside my article in the September 18, 1951 issue of the Gospel Herald, “Revival in Franconia” and John E. Lapp’s article “Revival Blessings in Franconia Conference” in the December 1951 Christian Monitor, little has been written. Here and there are references, for example:

Beulah Stauffer Hostetler in her book American Mennonites and Protestant Movements observed that George and Lawrence Brunk were Mennonite echoes of mass revivals sweeping through American Protestantism in the early fifties. She further observed that early in the twentieth century consecration was associated with plain clothes. The mass revival reinforced that emphasis. She noted that some persons became entranced with the evangelists, slighting local leaders. After these mass revivals “local congregational revivals decreased markedly.” (pages 279-287).

Clyde G. Kratz made an extended study of the Brunk Revival as part of his work at Eastern Mennonite Seminary, 1985. His research paper “Mixed Blessings”, however, has not been published.

Since the writing of this article in 2001, a few items have been published online, including a sermon (audio and transcription) by George Brunk: https://mla.bethelks.edu/ml-archive/2002sept/brunk.php and an essay on the influence of Billy Graham and how his style was emulated by the Brunks and other Anabaptist evangelists: https://anabaptisthistorians.org/2018/03/08/americas-pastor-among-the-quiet-in-the-land-billy-graham-and-north-american-anabaptists-part-i/

Paul M. Lederach (1925-2014) was a bishop of the Franconia Conference, ordained in 1949. From 1952 to 1978, he was associated with Mennonite Publishing House, Scottdale, PA, in several roles, and from 1978 to 1985, had an insurance business in Scottdale. Paul returned to the Franconia Conference in 1986 and became pastor of Franconia Mennonite Church. He was later chairman of the Franconia Conference overseers and interim pastor in several local congregations.