Mennonites and Alcohol

Written by Forrest Moyer on November 8, 2018

Recently the MHC participated in a pop-up exhibit at the Free Library of Philadelphia, called “Drinks in the Archives”. The event was part of Archives Month Philly, an annual month-long celebration of the rich archival resources in the Philadelphia region. The evening brought together sixteen archives and nine departments of the Free Library, to share items from their collections that relate to beverage creation and consumption.

Photos courtesy of Free Library of Philadelphia.

The Mennonite Heritage Center’s display focused on “Rural Germans and Drink” (MHC archivist Forrest Moyer pictured below). Across the aisle was a display by the German Society of Pennsylvania, which highlighted the urban German experience, including a history of breweries.

Below is a summary of our exhibit and a few recipes that we shared with visitors.

Rural Germans and Drink

Germans in the Philadelphia countryside, whose identities tended to be religious—Mennonite, Brethren, Lutheran, Reformed, etc.—tried to live pious and conscientious lives. In early years, distilling and moderate alcohol consumption were part of life; most German farmers made wine and cider for use at home through the 19th century. They also enjoyed non-alcoholic drinks such as peppermint water and garden tea for refreshment on hot summer days. As the Evangelical movement grew, strict temperance became the dominant view, especially among Mennonites and Brethren. Today, opposition has relaxed and it is not uncommon to find beer or wine at family picnics.

The oldest item in our display was an account book of Henry Wismer, a prosperous 18th-century Mennonite of Bedminster Township, Bucks County. Henry and son Abraham distilled whiskey and cordials in quantity for sale to neighbors. Their account books reside at the Mennonite Heritage Center (Hist. Mss. 162); gift of Norman M. Wismer.

Photo courtesy of Free Library of Philadelphia.

We included two manuscript recipes from this book in our handout; though we warned people that these recipes have not been tested! The first recipe, for a “cordial”, could be tested on a small scale (not 30 gallons!); the second recipe, a tonic for consumption, obviously is not the best way to treat disease in the 21st century. In the 18th century, many people followed recipes to make their own medicines and tonics at home.

A Recipe to Make Cordial

translated from German

Take 30 gallons of brandywine, take one ounce of nutmeg, one ounce of cloves and one ounce of cinnamon. Crush them fine in a mortar or grind them in a pepper mill. Take 20 pounds of sugar and 8 gallons of water and boil in a copper kettle. Skim this well and put it into the barrel while hot. Clean out the kettle well and put the brandywine in it, together with a quart and a pint of fennel seed and 10 or 12 sprigs of rosemary. Be careful and when the sugar water is in the barrel add the spices. Stir it a little with a stick and then close it tight.

—Henry Wismer account book, circa 1769

A Drink for Consumption

translated from German

Lungwort, liverwort, mullein, hyssop, watercress and agrimony, a handful of each; sweetwood root, elecampane root, fennel root, a half handful of each. All should be cut up coarsely and dried a little at first. Then mix with 4 quarts of barley water and boil until one pint is boiled off. Then when it is strained mix the drink with three spoonsful of honey to sweeten it. Then drink a gill every morning and evening, first warming it. Note well: This is a good drink for consumption. —Henry Wismer account book, circa 1769

Another section of the display featured a medicine bottle from Drs. Groff & Keeler in Harleysville, circa 1880; an advertisement for Groff & Keeler, “dealers in drugs and chemicals, standard patent medicines,…pure wines and liquors for medicinal uses” (both items gift of Isaac Clarence Kulp); and a porcelain medicine dispenser in the shape of gilt bird, circa 1870, from the Lederach family of Lower Salford Township (gift of Mary Jane Lederach Hershey), probably used to entice children to take medicine.

Photo courtesy of Free Library of Philadelphia.

The “Family Temperance Pledge” in the picture above was a common feature of Victorian-era family Bibles used by local Mennonite families. Rarely were the pledges signed, but they represent a time when the Evangelical and Temperance movements persuaded many Mennonites to cease producing and drinking alcohol.

Even during Temperance and Prohibition years, however, many local people continued to make wine from grapes, elderberries and dandelion in small batches for use at home. Here’s a dandelion wine recipe that has been tested and is safe to try:

Dandelion Wine

Take 6 qts dandelion blossoms

Take 4 qts water

Soak 3 days and 3 nights

Strain

Add 4 lbs white sugar, 3 sliced oranges, 3 sliced lemons, 2 tbs. or 2 cakes dry yeast

Let stand 4 days and 4 nights

Strain

Bottle. Do not tighten caps until all fermentation stops. It may take 2-3 weeks depending on temperature and quantity. It gets good around Christmas.

—Ronald Treichler, Goschenhoppen Historians Folk Festival Recipes (1980)

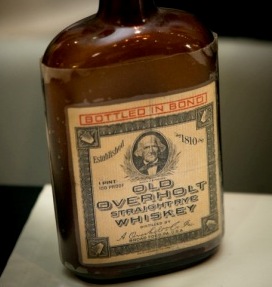

Perhaps the most frequently asked-about object in our display was this (empty) bottle of Old Overholt Whiskey, with its portrait of “Old Overholt” himself — Mennonite church trustee and successful distiller Abraham Overholt (1784-1870) of West Overton, PA (near Pittsburgh). Gift of Gerald Studer, former pastor of Scottdale Mennonite Church.

Perhaps the most frequently asked-about object in our display was this (empty) bottle of Old Overholt Whiskey, with its portrait of “Old Overholt” himself — Mennonite church trustee and successful distiller Abraham Overholt (1784-1870) of West Overton, PA (near Pittsburgh). Gift of Gerald Studer, former pastor of Scottdale Mennonite Church.

Abraham Overholt was born in Bucks County, but moved to western Pennsylvania as a teenager with his parents. He built a distillery at West Overton that was six stories high, 100 feet long, and could produce 860 gallons a day. Later his grandson, coal and steel magnate Henry Clay Frick, owned the company for a time.

The Old Overholt brand survived Prohibition and is produced today by Jim Beam (now Beam Suntory of Osaka, Japan), but it is not 100 proof straight rye whiskey as it was in Overholt’s time. It is a corn-rich Kentucky style. Overholt’s whiskey (and other Pennsylvania straight ryes) were “not a whiskey for gentlemen of elegant leisure to sip on the verandah. Sharp and stimulating, it’s a fuel for work and talk and invention,” according to David Wondrich, in his article “How Pennsylvania Rye Whiskey Lost Its Way”.

Wondrich’s statement helps paint a picture of the early Mennonite farmers of Pennsylvania, who distilled these spirits to keep their internal engines going as they cleared land of huge trees, planted and harvested by hand, and used liquor for medicinal needs. As technology improved and work became somewhat less physical in the 20th century, it makes sense that concern about over-consumption and temperance would outweigh the need for a fiery fuel.

For a summary of historic Anabaptist/Mennonite views on alcohol back to the 1500s, see: https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Alcohol_(1958)