Cynthia Yoder’s “Crazy Quilt”

Written by Forrest Moyer on July 6, 2017

A beautifully-written local memoir is now available on Kindle. If you’re interested in 20th-century Mennonite culture, this is a great read. You can purchase the book here.

Cynthia Yoder was a graduate student in New York City when she began to suffer from depression. Crazy Quilt follows her quest for meaning — a return to Berks County, PA, and visits with her grandparents, Henry and Elizabeth “Betts” Kulp Yoder. Enjoy the excerpts below.

…One night on the phone with my mother, I revisited a very impractical idea that I’d had the year before. I could head home and collect stories from my Pennsylvania Dutch Mennonite family.

“That sounds workable,” Mom said, always the optimist, bouncy as her brown bob. The fact that I had just derailed myself from my career track didn’t seem to phase her.

“I imagine one of the aunts and uncles might be willing to rent out a room — for a fair rate,” she said. I could see the wheel in her blue sky turning. I talked about staying with her parents, who lived on a farm north of Philadelphia. I had spent loads of time on the farm as a child, and envisioned lying in a haystack, writing out my stories, the cows grumbling in the barn below. But my grandmother was suffering her own depression, and my mother and I agreed it would be too confusing.

When Mom called back later and said she’d found an arrangement for living near my dad’s parents, I felt that perhaps a god was looking out for me after all: her name was Mom. I would stay with my dad’s twin, Roy, and his wife Sandi, who lived next door to my grandparents, Henry and Betts Yoder, on Kulp Hill. My aunt and uncle had a basement apartment that was empty, and they were willing to accomodate me.

I realize hanging out with one’s family can actually tip a wobbling sanity in the wrong direction. But I felt drawn to what I suspected was a simpler life than the one I’d been living in New York.

Henry and Betts, now in their early eighties, came from generations of Mennonites who saw themselves as separate from the world and so took their changes slowly. I, on the other hand, had stripped off my childhood culture in quick teenage gestures. I was all new, not given to looking back at old ways and old times. Perhaps that’s why my grandparents’ lives intrigued me so much. Their lives were based on roots, while my life was based on change. The heritage I had abandoned was as solid as the Hill my family had come to so many years ago, their belongings strapped to a horse-drawn wagon.

Henry and Betts, now in their early eighties, came from generations of Mennonites who saw themselves as separate from the world and so took their changes slowly. I, on the other hand, had stripped off my childhood culture in quick teenage gestures. I was all new, not given to looking back at old ways and old times. Perhaps that’s why my grandparents’ lives intrigued me so much. Their lives were based on roots, while my life was based on change. The heritage I had abandoned was as solid as the Hill my family had come to so many years ago, their belongings strapped to a horse-drawn wagon.

So I went, click-click, like Dorothy in her ruby slippers. Jonathan and I broke down our Upper West Side apartment, sold our random furnishings to neighboring Columbia University students, and boxed up the rest for storage. He went to live with friends. I set up shop in Bally, Pennsylvania, to tether myself to the fat root of my family and to the black soil of Kulp Hill.

From the chapter, “When I Was a Boy”:

From the chapter, “When I Was a Boy”:

“Ach, there’s another thing,” Betts said, frowning and waving her hand as if to shoo away a fly. “If the parents couldn’t hardly afford to take care of their children, feed and clothe them, they were put out on a farm. Your brother Norman,” she said to Henry, “he was only eight when he was sent. Imagine. He said he had terrible homesickness. When you were hired out to the Huber family in Spring City, you were fourteen.”

Henry responded slowly. “Yes, I was fourteen then.”

I had heard this before, but it still blew me away. Hiring your children out to a farm? In this century?

“Tell how far you’d go.” Betts tried to push him beyond his halting answer.

Pointing to the palm of his hand as a map, my grandfather dutifully showed the route.

“I’d go from Allentown to Norristown by trolley,” he said. “In Norristown, I’d get the train to Spring City. That was my way of going. But not often. I didn’t have the fare money.”

“Why were you hired out?” I asked. Although this part of Henry’s childhood was known among my family members, the why of it was never part of the story. “Why” remained an unplowed row at the edge of the field.

Henry replied, “I helped the Hubers on their farm—chores and such. They called it the little hire.”

“You always said you were there for your keep—for room and board,” Betts said, leaning toward him, her elbow on her armrest. She could barely contain herself. Now that we had him talking, she couldn’t get enough.

“Your parents were so poor they couldn’t afford to feed you?” I asked, incredulously. I put down my pen, not wanting Henry to be scared by the act of recording.

“I don’t know,” Betts said, looking down at the floor.

“I guess that was it,” Henry replied, noncommittal, again swiveling his chair slightly. “My pop drove a baker’s route, and he was getting ten dollars a week, plus raised goods. Raised goods included bread.”

“Buns,” Betts added.

“No,” Henry countered. “Buns were a luxury. At any rate, he was getting ten dollars a week. And I was one extra to feed. I guess that’s what it was.”

“Well, if you could feed one child off a loaf, you could feed two,” Betts snapped.

She didn’t take stock in his story.

Turning to me, she confided, “With the stepmother, it didn’t go so well. She favored her own girls.”

I looked at Henry. He was tapping his fingers against the armrests of his chair. Henry’s mother had died seven days after he was born, after complications from childbirth. Several years later, his father had married, and they had two girls of their own. I’d never heard that they were poor. Struggling, yes, but not poor. Henry didn’t say a word.

“We didn’t have bad feelings for my sisters,” he said, finally. “We always called them sisters. In any case, you weren’t paid as a hired boy. You’d work on the farm for room and board.”

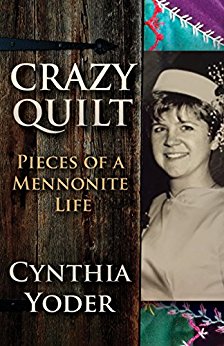

Henry and Elizabeth Yoder with sons Henry Paul, Harold, and twins Roy and Ray, circa 1943. Three of the boys became Mennonite ministers, including Cynthia’s father, Ray.